The Paradox of Fight Club

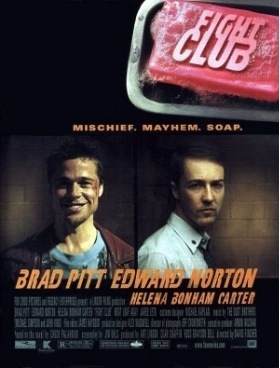

Posted by Andrew on October 15th, 2009 It was ten years ago today that Fight Club was released. Both the film and the book by Chuck Palahniuk explored a variety of themes. Besides the intricacies of soap making, starting your own cult and the downside of consumer culture, at its heart is a story about a man with a strange condition that causes him to develop an alternate personality. In psychological parlance, that’s called dissociative identity disorder or multiple personality disorder.

It was ten years ago today that Fight Club was released. Both the film and the book by Chuck Palahniuk explored a variety of themes. Besides the intricacies of soap making, starting your own cult and the downside of consumer culture, at its heart is a story about a man with a strange condition that causes him to develop an alternate personality. In psychological parlance, that’s called dissociative identity disorder or multiple personality disorder.

In the book and film this alternative personality resulting from this disorder was quite liberating for the main character.

Many people have asked if this is even a real condition. Prior to the 19th century people who displayed radically different personalities were assumed to be possessed. In the 19th century it was explored on somewhat more scientific, if not rigorous grounds. From Wikipedia:

These conversion disorders were found to occur in even the most resilient individuals, but with profound effect in someone with emotional instability like Louis Vivé (1863-?) who suffered a traumatic experience as a 13 year-old when he encountered a viper. Vivé was the subject of countless medical papers and became the most studied case of dissociation in the nineteenth century.

That was all it took for writers from Mary Shelley to Edgar Allen Poe to start running with the concept of one person inhabited by two or more personalities.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jeckyll and Mr Hyde explored the notion of an alter ego acting entirely on the impulses of your id.

Fight Club in many ways is a descendent of these concepts. Both Mr Hyde and Tyler Durden displayed extremely anti-social behavior – the exception being in Tyler Durden’s case, author Chuck Palahniuk created a narrative structure that made it justifiable from the assumed point of view.

Fight Club in many ways is a descendent of these concepts. Both Mr Hyde and Tyler Durden displayed extremely anti-social behavior – the exception being in Tyler Durden’s case, author Chuck Palahniuk created a narrative structure that made it justifiable from the assumed point of view.

Despite case studies giving some credence to the condition and the plethora of scientific rationales provided, some remained skeptical. A number of researchers who initially believed the condition to be genuine began to second guess that assumption when they paid closer attention to some of the more celebrated cases of the field’s pioneer Jean-Martin Charcot. From Wikipedia:

In the early 20th century interest in dissociation and DID waned for a number of reasons. After Charcot’s death in 1893, many of his “hysterical” patients were exposed as frauds and Janet’s association with Charcot tarnished his theories of dissociation. Sigmund Freud recanted his earlier emphasis on dissociation and childhood trauma.

Eventually the book the Many Faces of Eve published in 1957 and the film adaptation caused a resurgence in diagnosis of the condition as did the book and later film Sybil did in 1974. From Wikipedia:

Skeptics claim that people who present with the appearance of alleged multiple personality may have learned to exhibit the symptoms in return for social reinforcement. One case cited as an example for this viewpoint is the “Sybil” case, popularized by the news media. Psychiatrist Herbert Spiegel stated that “Sybil” had been provided with the idea of multiple personalities by her treating psychiatrist, Cornelia Wilbur, to describe states of feeling with which she was unfamiliar.

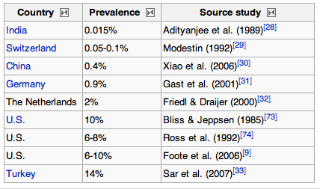

It’s particularly interesting how uniquely American this condition is (unless you buy into the premise that hyper-consumerism was the flashpoint for developing a split personality in Fight Club). From Wikipedia, figures from psychiatric populations (inpatients and outpatients) show a wide diversity from different countries putting the legitimacy of the condition under suspicion.

It’s particularly interesting how uniquely American this condition is (unless you buy into the premise that hyper-consumerism was the flashpoint for developing a split personality in Fight Club). From Wikipedia, figures from psychiatric populations (inpatients and outpatients) show a wide diversity from different countries putting the legitimacy of the condition under suspicion.

Despite the clinical controversy over this condition, there remains a fascination in many of us over the idea of developing a stronger personality capable of doing the things we’re unable to bring ourselves to do.

Despite the clinical controversy over this condition, there remains a fascination in many of us over the idea of developing a stronger personality capable of doing the things we’re unable to bring ourselves to do.

It’s that fascination with alternative personalities and the expression of free will in Fight Club that still resonates today. We know what it is, but we just don’t know how to express it. Weight loss and substance abuse treatment are billion-dollar industries because we can’t quite get our bodies and minds to agree on things.

It’s that fascination with alternative personalities and the expression of free will in Fight Club that still resonates today. We know what it is, but we just don’t know how to express it. Weight loss and substance abuse treatment are billion-dollar industries because we can’t quite get our bodies and minds to agree on things.

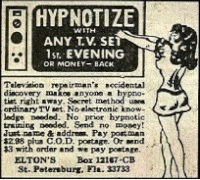

Where Hyde and Durden were expressions of the id, self-hypnosis and pseudo-psychology like NLP offer the promise of giving you control over your id to allow your higher functioning free will the ability to overcome your animal instincts.

Is the next desired evolution in mankind, not a physical one, but the ability to actually do the things we want?

Jeckyll and Hyde was about a Victorian scientist who may have been a bit repressed. Fight Club was the story of an everyman who felt emasculated by modern civilization. For both of them, part of their expression involved extreme violence and unleashing the id. Arguably in Durden’s case the violence (in particular the destruction of private property) was a byproduct of the world not being the way he wanted it to be and not something done for the sole sake of violence.

The lesson we can learn from Fight Club (we’ll pass over its conflicted view of personal freedom and anti-Capitalist message) and Jeckyll and Hyde is that the more civilized man is, the more frustrated he is by his inability to exert complete free will over his actions. So frustrated that he’s willing to start cults that destroy individuality and embrace violence to let that inner animal out to wreak havoc.

On one level Fight Club is about setting loose our id to unleash its fury that it can’t express itself in a less id-like way. And that is what we call a paradox.

link: Dissociative identity disorder – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

January 17th, 2010 at 8:54 pm

Hello. I found your article very interesting. However, I don't necessarily agree with you when you say, “It’s particularly interesting how uniquely American this condition is (unless you buy into the premise that hyper-consumerism was the flashpoint for developing a split personality in Fight Club). ” If you remember, there is a scene when “Tyler” is in the bathtub and Norton's character is clipping his nails I believe, on the floor of the bathroom on Paper St.; as they're talking, they both briefly reminisce about their dysfunctional relationship(s) with their father. Going along with the way the film only hints here and there at the big psychological disorder that, as it ends up, has been staring you in the face, I saw this as a suggestion of a traumatic (family) background, which goes right along with the findings of modern research on DID. I see this more as a reflection on whatever “flashpoint(s)” their might have been in the character's past, rather than the hyper-consumerism that consumes the split off personality in the character's adult life.

Just my two cents.

Thanks,

Beth

January 18th, 2010 at 2:54 am

Hello. I found your article very interesting. However, I don't necessarily agree with you when you say, “It’s particularly interesting how uniquely American this condition is (unless you buy into the premise that hyper-consumerism was the flashpoint for developing a split personality in Fight Club). ” If you remember, there is a scene when “Tyler” is in the bathtub and Norton's character is clipping his nails I believe, on the floor of the bathroom on Paper St.; as they're talking, they both briefly reminisce about their dysfunctional relationship(s) with their father. Going along with the way the film only hints here and there at the big psychological disorder that, as it ends up, has been staring you in the face, I saw this as a suggestion of a traumatic (family) background, which goes right along with the findings of modern research on DID. I see this more as a reflection on whatever “flashpoint(s)” their might have been in the character's past, rather than the hyper-consumerism that consumes the split off personality in the character's adult life.

Just my two cents.

Thanks,

Beth